Transform your business growth with Parramatta digital marketing Our strategies enhance visibility, attract targeted traffic, and maximise conversions for sustained success Partner with us for measurable digital marketing outcomes today

Maximise your business potential with Best SEO agency Parramatta We deliver impactful strategies designed to boost your brand awareness, improve online visibility, and generate a steady flow of qualified leads in Parramatta

Choose excellence in digital marketing with SEO expert Parramatta Our proven approaches drive website traffic, enhance customer engagement, and significantly improve conversion rates, supporting long-term business success in Parramatta

Best SEO Agency Parramatta Australia. Best SEO Parramatta Agency.Experience outstanding online performance through Responsive web design Parramatta Our expert team specialises in delivering solutions that improve rankings, drive engagement, and generate valuable leads for consistent business growth in Parramatta

Choose excellence in digital marketing with Small business SEO Parramatta Our proven approaches drive website traffic, enhance customer engagement, and significantly improve conversion rates, supporting long-term business success in Parramatta

Take your digital presence further with Web development Parramatta We develop custom strategies aimed at increasing your online visibility, improving search engine rankings, and achieving sustainable growth for your Parramatta-based business

Effective Web Design Parramatta Sydney.Choose excellence in digital marketing with SEO consultant Parramatta Our proven approaches drive website traffic, enhance customer engagement, and significantly improve conversion rates, supporting long-term business success in Parramatta

Choose excellence in digital marketing with Website designers Parramatta Our proven approaches drive website traffic, enhance customer engagement, and significantly improve conversion rates, supporting long-term business success in Parramatta

Choose excellence in digital marketing with SEO company Parramatta Our proven approaches drive website traffic, enhance customer engagement, and significantly improve conversion rates, supporting long-term business success in Parramatta

Digital Marketing Parramatta .

Take your digital presence further with Web design company Parramatta We develop custom strategies aimed at increasing your online visibility, improving search engine rankings, and achieving sustainable growth for your Parramatta-based business

Choose excellence in digital marketing with SEO audit Parramatta Our proven approaches drive website traffic, enhance customer engagement, and significantly improve conversion rates, supporting long-term business success in Parramatta

Choose excellence in digital marketing with Parramatta web developers Our proven approaches drive website traffic, enhance customer engagement, and significantly improve conversion rates, supporting long-term business success in Parramatta

Experience outstanding online performance through Professional SEO Parramatta Our expert team specialises in delivering solutions that improve rankings, drive engagement, and generate valuable leads for consistent business growth in Parramatta

Choose excellence in digital marketing with Parramatta WordPress developers Our proven approaches drive website traffic, enhance customer engagement, and significantly improve conversion rates, supporting long-term business success in Parramatta

Maximise your business potential with Technical SEO Parramatta We deliver impactful strategies designed to boost your brand awareness, improve online visibility, and generate a steady flow of qualified leads in Parramatta

Maximise your business potential with SEO for trades Parramatta We deliver impactful strategies designed to boost your brand awareness, improve online visibility, and generate a steady flow of qualified leads in Parramatta

Maximise your business potential with Mobile-friendly web design Parramatta We deliver impactful strategies designed to boost your brand awareness, improve online visibility, and generate a steady flow of qualified leads in Parramatta

Take your digital presence further with Lead generation Parramatta We develop custom strategies aimed at increasing your online visibility, improving search engine rankings, and achieving sustainable growth for your Parramatta-based business

Maximise your business potential with Parramatta SEO packages We deliver impactful strategies designed to boost your brand awareness, improve online visibility, and generate a steady flow of qualified leads in Parramatta

Choose excellence in digital marketing with On-page SEO Parramatta Our proven approaches drive website traffic, enhance customer engagement, and significantly improve conversion rates, supporting long-term business success in Parramatta

Choose excellence in digital marketing with SEO and web design Parramatta Our proven approaches drive website traffic, enhance customer engagement, and significantly improve conversion rates, supporting long-term business success in Parramatta

|

|

|

Screenshot

The Main Page of the English Wikipedia running an alpha version of MediaWiki 1.40

|

|

| Original author(s) | |

|---|---|

| Developer(s) | Wikimedia Foundation |

| Initial release | January 25, 2002 |

| Stable release |

1.43.0[1]

|

| Repository | |

| Written in | PHP[2] |

| Operating system | Windows, macOS, Linux, FreeBSD, OpenBSD, Solaris |

| Size | 79.05 MiB (compressed) |

| Available in | 459[3] languages |

| Type | Wiki software |

| License | GPLv2+[4] |

| Website | mediawiki |

MediaWiki is free and open-source wiki software originally developed by Magnus Manske for use on Wikipedia on January 25, 2002, and further improved by Lee Daniel Crocker,[5][6] after which development has been coordinated by the Wikimedia Foundation. It powers several wiki hosting websites across the Internet, as well as most websites hosted by the Wikimedia Foundation including Wikipedia, Wiktionary, Wikimedia Commons, Wikiquote, Meta-Wiki and Wikidata, which define a large part of the set requirements for the software.[7] Besides its usage on Wikimedia sites, MediaWiki has been used as a knowledge management and content management system on websites such as Fandom, wikiHow and major internal installations like Intellipedia and Diplopedia.

MediaWiki is written in the PHP programming language and stores all text content into a database. The software is optimized to efficiently handle large projects, which can have terabytes of content and hundreds of thousands of views per second.[7][8] Because Wikipedia is one of the world's largest and most visited websites, achieving scalability through multiple layers of caching and database replication has been a major concern for developers. Another major aspect of MediaWiki is its internationalization; its interface is available in more than 400 languages.[9] The software has hundreds of configuration settings[10] and more than 1,000 extensions available for enabling various features to be added or changed.[11]

MediaWiki provides a rich core feature set and a mechanism to attach extensions to provide additional functionality.

Due to the strong emphasis on multilingualism in the Wikimedia projects, internationalization and localization has received significant attention by developers. The user interface has been fully or partially translated into more than 400 languages on translatewiki.net,[9] and can be further customized by site administrators (the entire interface is editable through the wiki).

Several extensions, most notably those collected in the MediaWiki Language Extension Bundle, are designed to further enhance the multilingualism and internationalization of MediaWiki.

Installation of MediaWiki requires that the user have administrative privileges on a server running both PHP and a compatible type of SQL database. Some users find that setting up a virtual host is helpful if the majority of one's site runs under a framework (such as Zope or Ruby on Rails) that is largely incompatible with MediaWiki.[12] Cloud hosting can eliminate the need to deploy a new server.[13]

An installation PHP script is accessed via a web browser to initialize the wiki's settings. It prompts the user for a minimal set of required parameters, leaving further changes, such as enabling uploads,[14] adding a site logo,[15] and installing extensions, to be made by modifying configuration settings contained in a file called LocalSettings.php.[16] Some aspects of MediaWiki can be configured through special pages or by editing certain pages; for instance, abuse filters can be configured through a special page,[17] and certain gadgets can be added by creating JavaScript pages in the MediaWiki namespace.[18] The MediaWiki community publishes a comprehensive installation guide.[19]

One of the earliest differences between MediaWiki (and its predecessor, UseModWiki) and other wiki engines was the use of "free links" instead of CamelCase. When MediaWiki was created, it was typical for wikis to require text like "WorldWideWeb" to create a link to a page about the World Wide Web; links in MediaWiki, on the other hand, are created by surrounding words with double square brackets, and any spaces between them are left intact, e.g. [[World Wide Web]]. This change was logical for the purpose of creating an encyclopedia, where accuracy in titles is important.

MediaWiki uses an extensible[20] lightweight wiki markup designed to be easier to use and learn than HTML. Tools exist for converting content such as tables between MediaWiki markup and HTML.[21] Efforts have been made to create a MediaWiki markup spec, but a consensus seems to have been reached that Wikicode requires context-sensitive grammar rules.[22][23] The following side-by-side comparison illustrates the differences between wiki markup and HTML:

| MediaWiki syntax (the "behind the scenes" code used to add formatting to text) |

HTML equivalent (another type of "behind the scenes" code used to add formatting to text) |

Rendered output (seen onscreen by a site viewer) |

|---|---|---|

====A dialogue====

"Take some more [[tea]]," the March Hare said to Alice, very earnestly.

"I've had nothing yet," Alice replied in an offended tone: "so I can't take more."

"You mean you can't take ''less''," said the Hatter: "it's '''very''' easy to take ''more'' than nothing."

|

<h4>A dialogue</h4>

<p>"Take some more <a href="/wiki/Tea" title="Tea">tea</a>," the March Hare said to Alice, very earnestly.</p> <br>

<p>"I've had nothing yet," Alice replied in an offended tone: "so I can't take more."</p> <br>

<p>"You mean you can't take <i>less</i>," said the Hatter: "it's <b>very</b> easy to take <i>more</i> than nothing."</p>

|

A dialogue

"Take some more tea," the March Hare said to Alice, very earnestly. "I've had nothing yet," Alice replied in an offended tone: "so I can't take more." "You mean you can't take less," said the Hatter: "it's very easy to take more than nothing." |

(Quotation above from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll)

MediaWiki's default page-editing tools have been described as somewhat challenging to learn.[24] A survey of students assigned to use a MediaWiki-based wiki found that when they were asked an open question about main problems with the wiki, 24% cited technical problems with formatting, e.g. "Couldn't figure out how to get an image in. Can't figure out how to show a link with words; it inserts a number."[25]

To make editing long pages easier, MediaWiki allows the editing of a subsection of a page (as identified by its header). A registered user can also indicate whether or not an edit is minor. Correcting spelling, grammar or punctuation are examples of minor edits, whereas adding paragraphs of new text is an example of a non-minor edit.

Sometimes while one user is editing, a second user saves an edit to the same part of the page. Then, when the first user attempts to save the page, an edit conflict occurs. The second user is then given an opportunity to merge their content into the page as it now exists following the first user's page save.

MediaWiki's user interface has been localized in many different languages. A language for the wiki content itself can also be set, to be sent in the "Content-Language" HTTP header and "lang" HTML attribute.

VisualEditor has its own integrated wikitext editing interface known as 2017 wikitext editor, the older editing interface is known as 2010 wikitext editor.

MediaWiki has an extensible web API (application programming interface) that provides direct, high-level access to the data contained in the MediaWiki databases. Client programs can use the API to log in, get data, and post changes. The API supports thin web-based JavaScript clients and end-user applications (such as vandal-fighting tools). The API can be accessed by the backend of another web site.[26] An extensive Python bot library, Pywikibot,[27] and a popular semi-automated tool called AutoWikiBrowser, also interface with the API.[28] The API is accessed via URLs such as https://en.wikipedia.org/w/api.php?action=query&list=recentchanges. In this case, the query would be asking Wikipedia for information relating to the last 10 edits to the site. One of the perceived advantages of the API is its language independence; it listens for HTTP connections from clients and can send a response in a variety of formats, such as XML, serialized PHP, or JSON.[29] Client code has been developed to provide layers of abstraction to the API.[30]

Among the features of MediaWiki to assist in tracking edits is a Recent Changes feature that provides a list of recent edits to the wiki. This list contains basic information about those edits such as the editing user, the edit summary, the page edited, as well as any tags (e.g. "possible vandalism")[31] added by customizable abuse filters and other extensions to aid in combating unhelpful edits.[32] On more active wikis, so many edits occur that it is hard to track Recent Changes manually. Anti-vandal software, including user-assisted tools,[33] is sometimes employed on such wikis to process Recent Changes items. Server load can be reduced by sending a continuous feed of Recent Changes to an IRC channel that these tools can monitor, eliminating their need to send requests for a refreshed Recent Changes feed to the API.[34][35]

Another important tool is watchlisting. Each logged-in user has a watchlist to which the user can add whatever pages he or she wishes. When an edit is made to one of those pages, a summary of that edit appears on the watchlist the next time it is refreshed.[36] As with the recent changes page, recent edits that appear on the watchlist contain clickable links for easy review of the article history and specific changes made.

There is also the capability to review all edits made by any particular user. In this way, if an edit is identified as problematic, it is possible to check the user's other edits for issues.

MediaWiki allows one to link to specific versions of articles. This has been useful to the scientific community, in that expert peer reviewers could analyse articles, improve them and provide links to the trusted version of that article.[37]

Navigation through the wiki is largely through internal wikilinks. MediaWiki's wikilinks implement page existence detection, in which a link is colored blue if the target page exists on the local wiki and red if it does not. If a user clicks on a red link, they are prompted to create an article with that title. Page existence detection makes it practical for users to create "wikified" articles—that is, articles containing links to other pertinent subjects—without those other articles being yet in existence.

Interwiki links function much the same way as namespaces. A set of interwiki prefixes can be configured to cause, for instance, a page title of wikiquote:Jimbo Wales to direct the user to the Jimbo Wales article on Wikiquote.[38] Unlike internal wikilinks, interwiki links lack page existence detection functionality, and accordingly there is no way to tell whether a blue interwiki link is broken or not.

Interlanguage links are the small navigation links that show up in the sidebar in most MediaWiki skins that connect an article with related articles in other languages within the same Wiki family. This can provide language-specific communities connected by a larger context, with all wikis on the same server or each on its own server.[39]

Previously, Wikipedia used interlanguage links to link an article to other articles on the same topic in other editions of Wikipedia. This was superseded by the launch of Wikidata.[40]

Page tabs are displayed at the top of pages. These tabs allow users to perform actions or view pages that are related to the current page. The available default actions include viewing, editing, and discussing the current page. The specific tabs displayed depend on whether the user is logged into the wiki and whether the user has sysop privileges on the wiki. For instance, the ability to move a page or add it to one's watchlist is usually restricted to logged-in users. The site administrator can add or remove tabs by using JavaScript or installing extensions.[41]

Each page has an associated history page from which the user can access every version of the page that has ever existed and generate diffs between two versions of his choice. Users' contributions are displayed not only here, but also via a "user contributions" option on a sidebar. In a 2004 article, Carl Challborn and Teresa Reimann noted that "While this feature may be a slight deviation from the collaborative, 'ego-less' spirit of wiki purists, it can be very useful for educators who need to assess the contribution and participation of individual student users."[42]

MediaWiki provides many features beyond hyperlinks for structuring content. One of the earliest such features is namespaces. One of Wikipedia's earliest problems had been the separation of encyclopedic content from pages pertaining to maintenance and communal discussion, as well as personal pages about encyclopedia editors. Namespaces are prefixes before a page title (such as "User:" or "Talk:") that serve as descriptors for the page's purpose and allow multiple pages with different functions to exist under the same title. For instance, a page titled "[[The Terminator]]", in the default namespace, could describe the 1984 movie starring Arnold Schwarzenegger, while a page titled "[[User:The Terminator]]" could be a profile describing a user who chooses this name as a pseudonym. More commonly, each namespace has an associated "Talk:" namespace, which can be used to discuss its contents, such as "User talk:" or "Template talk:". The purpose of having discussion pages is to allow content to be separated from discussion surrounding the content.[43][44]

Namespaces can be viewed as folders that separate different basic types of information or functionality. Custom namespaces can be added by the site administrators. There are 16 namespaces by default for content, with 2 "pseudo-namespaces" used for dynamically generated "Special:" pages and links to media files. Each namespace on MediaWiki is numbered: content page namespaces have even numbers and their associated talk page namespaces have odd numbers.[45]

Users can create new categories and add pages and files to those categories by appending one or more category tags to the content text. Adding these tags creates links at the bottom of the page that take the reader to the list of all pages in that category, making it easy to browse related articles.[46] The use of categorization to organize content has been described as a combination of:

In addition to namespaces, content can be ordered using subpages. This simple feature provides automatic breadcrumbs of the pattern [[Page title/Subpage title]] from the page after the slash (in this case, "Subpage title") to the page before the slash (in this case, "Page title").

If the feature is enabled, users can customize their stylesheets and configure client-side JavaScript to be executed with every pageview. On Wikipedia, this has led to a large number of additional tools and helpers developed through the wiki and shared among users. For instance, navigation popups is a custom JavaScript tool that shows previews of articles when the user hovers over links and also provides shortcuts for common maintenance tasks.[48]

The entire MediaWiki user interface can be edited through the wiki itself by users with the necessary permissions (typically called "administrators"). This is done through a special namespace with the prefix "MediaWiki:", where each page title identifies a particular user interface message. Using an extension,[49] it is also possible for a user to create personal scripts, and to choose whether certain sitewide scripts should apply to them by toggling the appropriate options in the user preferences page.

The "MediaWiki:" namespace was originally also used for creating custom text blocks that could then be dynamically loaded into other pages using a special syntax. This content was later moved into its own namespace, "Template:".

Templates are text blocks that can be dynamically loaded inside another page whenever that page is requested. The template is a special link in double curly brackets (for example "Disputed"), which calls the template (in this case located at Template:Disputed) to load in place of the template call.

Templates are structured documents containing attribute–value pairs. They are defined with parameters, to which are assigned values when transcluded on an article page. The name of the parameter is delimited from the value by an equals sign. A class of templates known as infoboxes is used on Wikipedia to collect and present a subset of information about its subject, usually on the top (mobile view) or top right-hand corner (desktop view) of the document.

Pages in other namespaces can also be transcluded as templates. In particular, a page in the main namespace can be transcluded by prefixing its title with a colon; for example, :MediaWiki transcludes the article "MediaWiki" from the main namespace. Also, it is possible to mark the portions of a page that should be transcluded in several ways, the most basic of which are:[50]

<noinclude>...</noinclude>, which marks content that is not to be transcluded;<includeonly>...</includeonly>, which marks content that is not rendered unless it is transcluded;<onlyinclude>...</onlyinclude>, which marks content that is to be the only content transcluded.A related method, called template substitution (called by adding subst: at the beginning of a template link) inserts the contents of the template into the target page (like a copy and paste operation), instead of loading the template contents dynamically whenever the page is loaded. This can lead to inconsistency when using templates, but may be useful in certain cases, and in most cases requires fewer server resources (the actual amount of savings can vary depending on wiki configuration and the complexity of the template).

Templates have found many different uses. Templates enable users to create complex table layouts that are used consistently across multiple pages, and where only the content of the tables gets inserted using template parameters. Templates are frequently used to identify problems with a Wikipedia article by putting a template in the article. This template then outputs a graphical box stating that the article content is disputed or in need of some other attention, and also categorize it so that articles of this nature can be located. Templates are also used on user pages to send users standard messages welcoming them to the site,[51] giving them awards for outstanding contributions,[52][53] warning them when their behavior is considered inappropriate,[54] notifying them when they are blocked from editing,[55] and so on.

MediaWiki offers flexibility in creating and defining user groups. For instance, it would be possible to create an arbitrary "ninja" group that can block users and delete pages, and whose edits are hidden by default in the recent changes log. It is also possible to set up a group of "autoconfirmed" users that one becomes a member of after making a certain number of edits and waiting a certain number of days.[56] Some groups that are enabled by default are bureaucrats and sysops. Bureaucrats have the power to change other users' rights. Sysops have power over page protection and deletion and the blocking of users from editing. MediaWiki's available controls on editing rights have been deemed sufficient for publishing and maintaining important documents such as a manual of standard operating procedures in a hospital.[57]

MediaWiki comes with a basic set of features related to restricting access, but its original and ongoing design is driven by functions that largely relate to content, not content segregation. As a result, with minimal exceptions (related to specific tools and their related "Special" pages), page access control has never been a high priority in core development and developers have stated that users requiring secure user access and authorization controls should not rely on MediaWiki, since it was never designed for these kinds of situations. For instance, it is extremely difficult to create a wiki where only certain users can read and access some pages.[58] Here, wiki engines like Foswiki, MoinMoin and Confluence provide more flexibility by supporting advanced security mechanisms like access control lists.

The MediaWiki codebase contains various hooks using callback functions to add additional PHP code in an extensible way. This allows developers to write extensions without necessarily needing to modify the core or having to submit their code for review. Installing an extension typically consists of adding a line to the configuration file, though in some cases additional changes such as database updates or core patches are required.

Five main extension points were created to allow developers to add features and functionalities to MediaWiki. Hooks are run every time a certain event happens; for instance, the ArticleSaveComplete hook occurs after a save article request has been processed.[59] This can be used, for example, by an extension that notifies selected users whenever a page edit occurs on the wiki from new or anonymous users.[60] New tags can be created to process data with opening and closing tags (<newtag>...</newtag>).[61] Parser functions can be used to create a new command (#if:...).[62] New special pages can be created to perform a specific function. These pages are dynamically generated. For example, a special page might show all pages that have one or more links to an external site or it might create a form providing user submitted feedback.[63] Skins allow users to customize the look and feel of MediaWiki.[64] A minor extension point allows the use of Amazon S3 to host image files.[65]

Among the most popular extensions is a parser function extension, ParserFunctions, which allows different content to be rendered based on the result of conditional statements.[66] These conditional statements can perform functions such as evaluating whether a parameter is empty, comparing strings, evaluating mathematical expressions, and returning one of two values depending on whether a page exists. It was designed as a replacement for a notoriously inefficient template called Qif.[67] Schindler recounts the history of the ParserFunctions extension as follows:[68]

In 2006 some Wikipedians discovered that through an intricate and complicated interplay of templating features and CSS they could create conditional wiki text, i.e. text that was displayed if a template parameter had a specific value. This included repeated calls of templates within templates, which bogged down the performance of the whole system. The developers faced the choice of either disallowing the spreading of an obviously desired feature by detecting such usage and explicitly disallowing it within the software or offering an efficient alternative. The latter was done by Tim Starling, who announced the introduction of parser functions, wiki text that calls functions implemented in the underlying software. At first, only conditional text and the computation of simple mathematical expressions were implemented, but this already increased the possibilities for wiki editors enormously. With time further parser functions were introduced, finally leading to a framework that allowed the simple writing of extension functions to add arbitrary functionalities, like e.g. geo-coding services or widgets. This time the developers were clearly reacting to the demand of the community, being forced either to fight the solution of the issue that the community had (i.e. conditional text), or offer an improved technical implementation to replace the previous practice and achieve an overall better performance.

Another parser functions extension, StringFunctions, was developed to allow evaluation of string length, string position, and so on. Wikimedia communities, having created awkward workarounds to accomplish the same functionality,[69] clamored for it to be enabled on their projects.[70] Much of its functionality was eventually integrated into the ParserFunctions extension,[71] albeit disabled by default and accompanied by a warning from Tim Starling that enabling string functions would allow users "to implement their own parsers in the ugliest, most inefficient programming language known to man: MediaWiki wikitext with ParserFunctions."[72]

Since 2012 an extension, Scribunto, has existed that allows for the creation of "modules"—wiki pages written in the scripting language Lua—which can then be run within templates and standard wiki pages. Scribunto has been installed on Wikipedia and other Wikimedia sites since 2013 and is used heavily on those sites. Scribunto code runs significantly faster than corresponding wikitext code using ParserFunctions.[73]

Another very popular extension is a citation extension that enables footnotes to be added to pages using inline references.[74] This extension has, however, been criticized for being difficult to use and requiring the user to memorize complex syntax. A gadget called RefToolbar attempts to make it easier to create citations using common templates. MediaWiki has some extensions that are well-suited for academia, such as mathematics extensions[75] and an extension that allows molecules to be rendered in 3D.[76]

A generic Widgets extension exists that allows MediaWiki to integrate with virtually anything. Other examples of extensions that could improve a wiki are category suggestion extensions[77] and extensions for inclusion of Flash Videos,[78] YouTube videos,[79] and RSS feeds.[80] Metavid, a site that archives video footage of the U.S. Senate and House floor proceedings, was created using code extending MediaWiki into the domain of collaborative video authoring.[81]

There are many spambots that search the web for MediaWiki installations and add linkspam to them, despite the fact that MediaWiki uses the nofollow attribute to discourage such attempts at search engine optimization.[82] Part of the problem is that third party republishers, such as mirrors, may not independently implement the nofollow tag on their websites, so marketers can still get PageRank benefit by inserting links into pages when those entries appear on third party websites.[83] Anti-spam extensions have been developed to combat the problem by introducing CAPTCHAs,[84] blacklisting certain URLs,[85] and allowing bulk deletion of pages recently added by a particular user.[86]

MediaWiki comes pre-installed with a standard text-based search. Extensions exist to let MediaWiki use more sophisticated third-party search engines, including Elasticsearch (which since 2014 has been in use on Wikipedia), Lucene[87] and Sphinx.[88]

Various MediaWiki extensions have also been created to allow for more complex, faceted search, on both data entered within the wiki and on metadata such as pages' revision history.[89][90] Semantic MediaWiki is one such extension.[91][92]

Various extensions to MediaWiki support rich content generated through specialized syntax. These include mathematical formulas using LaTeX, graphical timelines over mathematical plotting, musical scores and Egyptian hieroglyphs.

The software supports a wide variety of uploaded media files, and allows image galleries and thumbnails to be generated with relative ease. There is also support for Exif metadata. MediaWiki operates the Wikimedia Commons, one of the largest free content media archives.

For WYSIWYG editing, VisualEditor is available to use in MediaWiki which simplifying editing process for editors and has been bundled since MediaWiki 1.35.[93] Other extensions exist for handling WYSIWYG editing to different degrees.[94]

MediaWiki can use either the MySQL/MariaDB, PostgreSQL or SQLite relational database management system. Support for Oracle Database and Microsoft SQL Server has been dropped since MediaWiki 1.34.[95] A MediaWiki database contains several dozen tables, including a page table that contains page titles, page ids, and other metadata;[96] and a revision table to which is added a new row every time an edit is made, containing the page id, a brief textual summary of the change performed, the user name of the article editor (or its IP address the case of an unregistered user) and a timestamp.[97][98]

In a 4½ year period prior to 2008, the MediaWiki database had 170 schema versions.[99] Possibly the largest schema change was done in 2005 with MediaWiki 1.5, when the storage of metadata was separated from that of content, to improve performance flexibility. When this upgrade was applied to Wikipedia, the site was locked for editing, and the schema was converted to the new version in about 22 hours. Some software enhancement proposals, such as a proposal to allow sections of articles to be watched via watchlist, have been rejected because the necessary schema changes would have required excessive Wikipedia downtime.[100]

Because it is used to run one of the highest-traffic sites on the Web, Wikipedia, MediaWiki's performance and scalability have been highly optimized.[101] MediaWiki supports Squid, load-balanced database replication, client-side caching, memcached or table-based caching for frequently accessed processing of query results, a simple static file cache, feature-reduced operation, revision compression, and a job queue for database operations. MediaWiki developers have attempted to optimize the software by avoiding expensive algorithms, database queries, etc., caching every result that is expensive and has temporal locality of reference, and focusing on the hot spots in the code through profiling.[102]

MediaWiki code is designed to allow for data to be written to a read-write database and read from read-only databases, although the read-write database can be used for some read operations if the read-only databases are not yet up to date. Metadata, such as article revision history, article relations (links, categories etc.), user accounts and settings can be stored in core databases and cached; the actual revision text, being more rarely used, can be stored as append-only blobs in external storage. The software is suitable for the operation of large-scale wiki farms such as Wikimedia, which had about 800 wikis as of August 2011. However, MediaWiki comes with no built-in GUI to manage such installations.

Empirical evidence shows most revisions in MediaWiki databases tend to differ only slightly from previous revisions. Therefore, subsequent revisions of an article can be concatenated and then compressed, achieving very high data compression ratios of up to 100×.[102]

For more information on the architecture, such as how it stores wikitext and assembles a page, see External links.

The parser serves as the de facto standard for the MediaWiki syntax, as no formal syntax has been defined. Due to this lack of a formal definition, it has been difficult to create WYSIWYG editors for MediaWiki, although several WYSIWYG extensions do exist, including the popular VisualEditor.

MediaWiki is not designed to be a suitable replacement for dedicated online forum or blogging software,[103] although extensions do exist to allow for both of these.[104][105]

It is common for new MediaWiki users to make certain mistakes, such as forgetting to sign posts with four tildes (~~~~),[106] or manually entering a plaintext signature,[107] due to unfamiliarity with the idiosyncratic particulars involved in communication on MediaWiki discussion pages. On the other hand, the format of these discussion pages has been cited as a strength by one educator, who stated that it provides more fine-grain capabilities for discussion than traditional threaded discussion forums. For example, instead of 'replying' to an entire message, the participant in a discussion can create a hyperlink to a new wiki page on any word from the original page. Discussions are easier to follow since the content is available via hyperlinked wiki page, rather than a series of reply messages on a traditional threaded discussion forum. However, except in few cases, students were not using this capability, possibly because of their familiarity with the traditional linear discussion style and a lack of guidance on how to make the content more 'link-rich'.[108]

MediaWiki by default has little support for the creation of dynamically assembled documents, or pages that aggregate data from other pages. Some research has been done on enabling such features directly within MediaWiki.[109] The Semantic MediaWiki extension provides these features. It is not in use on Wikipedia, but in more than 1,600 other MediaWiki installations.[110] The Wikibase Repository and Wikibase Repository client are however implemented in Wikidata and Wikipedia respectively, and to some extent provides semantic web features, and linking of centrally stored data to infoboxes in various Wikipedia articles.

Upgrading MediaWiki is usually fully automated, requiring no changes to the site content or template programming. Historically troubles have been encountered when upgrading from significantly older versions.[111]

MediaWiki developers have enacted security standards, both for core code and extensions.[112] SQL queries and HTML output are usually done through wrapper functions that handle validation, escaping, filtering for prevention of cross-site scripting and SQL injection.[113] Many security issues have had to be patched after a MediaWiki version release,[114] and accordingly MediaWiki.org states, "The most important security step you can take is to keep your software up to date" by subscribing to the announcement mailing list and installing security updates that are announced.[115]

Support for MediaWiki users consists of:

MediaWiki is free and open-source and is distributed under the terms of the GNU General Public License version 2 or any later version. Its documentation, located at its official website at www.mediawiki.org, is released under the Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 license, with a set of help pages intended to be freely copied into fresh wiki installations and/or distributed with MediaWiki software in the public domain instead to eliminate legal issues for wikis with other licenses.[119][120] MediaWiki's development has generally favored the use of open-source media formats.[121]

MediaWiki has an active volunteer community for development and maintenance. MediaWiki developers are spread around the world, though with a majority in the United States and Europe. Face-to-face meetings and programming sessions for MediaWiki developers have been held once or several times a year since 2004.[122]

Anyone can submit patches to the project's Git/Gerrit repository.[123] There are also paid programmers who primarily develop projects for the Wikimedia Foundation. MediaWiki developers participate in the Google Summer of Code by facilitating the assignment of mentors to students wishing to work on MediaWiki core and extension projects.[124] During the year prior to November 2012, there were about two hundred developers who had committed changes to the MediaWiki core or extensions.[125] Major MediaWiki releases are generated approximately every six months by taking snapshots of the development branch, which is kept continuously in a runnable state;[126] minor releases, or point releases, are issued as needed to correct bugs (especially security problems). MediaWiki is developed on a continuous integration development model, in which software changes are pushed live to Wikimedia sites on regular basis.[126] MediaWiki also has a public bug tracker, phabricator.wikimedia.org, which runs Phabricator. The site is also used for feature and enhancement requests.

When Wikipedia was launched in January 2001, it ran on an existing wiki software system, UseModWiki. UseModWiki is written in the Perl programming language, and stores all wiki pages in text (.txt) files. This software soon proved to be limiting, in both functionality and performance. In mid-2001, Magnus Manske—a developer and student at the University of Cologne, as well as a Wikipedia editor—began working on new software that would replace UseModWiki, specifically designed for use by Wikipedia. This software was written in the PHP scripting language, and stored all of its information in a MySQL database. The new software was largely developed by August 24, 2001, and a test wiki for it was established shortly thereafter.

The first full implementation of this software was the new Meta Wikipedia on November 9, 2001. There was a desire to have it implemented immediately on the English-language Wikipedia.[127] However, Manske was apprehensive about any potential bugs harming the nascent website during the period of the final exams he had to complete immediately prior to Christmas;[128] this led to the launch on the English-language Wikipedia being delayed until January 25, 2002. The software was then, gradually, deployed on all the Wikipedia language sites of that time. This software was referred to as "the PHP script" and as "phase II", with the name "phase I", retroactively given to the use of UseModWiki.

Increasing usage soon caused load problems to arise again, and soon after, another rewrite of the software began; this time being done by Lee Daniel Crocker, which became known as "phase III". This new software was also written in PHP, with a MySQL backend, and kept the basic interface of the phase II software, but with the added functionality of a wider scalability. The "phase III" software went live on Wikipedia in July 2002.

The Wikimedia Foundation was announced on June 20, 2003. In July, Wikipedia contributor Daniel Mayer suggested the name "MediaWiki" for the software, as a play on "Wikimedia".[129] The MediaWiki name was gradually phased in, beginning in August 2003. The name has frequently caused confusion due to its (intentional) similarity to the "Wikimedia" name (which itself is similar to "Wikipedia").[130] The first version of MediaWiki, 1.1, was released in December 2003.

The old product logo was created by Erik Möller, using a flower photograph taken by Florence Nibart-Devouard, and was originally submitted to the logo contest for a new Wikipedia logo, held from July 20 to August 27, 2003.[131][132] The logo came in third place, and was chosen to represent MediaWiki rather than Wikipedia, with the second place logo being used for the Wikimedia Foundation.[133] The double square brackets ([[ ]]) symbolize the syntax MediaWiki uses for creating hyperlinks to other wiki pages; while the sunflower represents the diversity of content on Wikipedia, its constant growth, and the wilderness.[134]

Later, Brooke Vibber, the chief technical officer of the Wikimedia Foundation,[135] took up the role of release manager.[136][101]

Major milestones in MediaWiki's development have included: the categorization system (2004); parser functions, (2006); Flagged Revisions, (2008);[68] the "ResourceLoader", a delivery system for CSS and JavaScript (2011);[137] and the VisualEditor, a "what you see is what you get" (WYSIWYG) editing platform (2013).[138]

The contest of designing a new logo was initiated on June 22, 2020, as the old logo was a bitmap image and had "high details", leading to problems when rendering at high and low resolutions, respectively. After two rounds of voting, the new and current MediaWiki logo designed by Serhio Magpie was selected on October 24, 2020, and officially adopted on April 1, 2021.[139]

MediaWiki's most famous use has been in Wikipedia and, to a lesser degree, the Wikimedia Foundation's other projects. Fandom, a wiki hosting service formerly known as Wikia, runs on MediaWiki. Other public wikis that run on MediaWiki include wikiHow and SNPedia. WikiLeaks began as a MediaWiki-based site, but is no longer a wiki.

A number of alternative wiki encyclopedias to Wikipedia run on MediaWiki, including Citizendium, Metapedia, Scholarpedia and Conservapedia. MediaWiki is also used internally by a large number of companies, including Novell and Intel.[140][141]

Notable usages of MediaWiki within governments include Intellipedia, used by the United States Intelligence Community, Diplopedia, used by the United States Department of State, and milWiki, a part of milSuite used by the United States Department of Defense. United Nations agencies such as the United Nations Development Programme and INSTRAW chose to implement their wikis using MediaWiki, because "this software runs Wikipedia and is therefore guaranteed to be thoroughly tested, will continue to be developed well into the future, and future technicians on these wikis will be more likely to have exposure to MediaWiki than any other wiki software."[142]

The Free Software Foundation uses MediaWiki to implement the LibrePlanet site.[143]

Users of online collaboration software are familiar with MediaWiki's functions and layout due to its noted use on Wikipedia. A 2006 overview of social software in academia observed that "Compared to other wikis, MediaWiki is also fairly aesthetically pleasing, though simple, and has an easily customized side menu and stylesheet."[144] However, in one assessment in 2006, Confluence was deemed to be a superior product due to its very usable API and ability to better support multiple wikis.[76]

A 2009 study at the University of Hong Kong compared TWiki to MediaWiki. The authors noted that TWiki has been considered as a collaborative tool for the development of educational papers and technical projects, whereas MediaWiki's most noted use is on Wikipedia. Although both platforms allow discussion and tracking of progress, TWiki has a "Report" part that MediaWiki lacks. Students perceived MediaWiki as being easier to use and more enjoyable than TWiki. When asked whether they recommended using MediaWiki for knowledge management course group project, 15 out of 16 respondents expressed their preference for MediaWiki giving answers of great certainty, such as "of course", "for sure".[145] TWiki and MediaWiki both have flexible plug-in architecture.[146]

A 2009 study that compared students' experience with MediaWiki to that with Google Docs found that students gave the latter a much higher rating on user-friendly layout.[147]

A 2021 study conducted by the Brazilian Nuclear Engineering Institute compared a MediaWiki-based knowledge management system against two others that were based on DSpace and Open Journal Systems, respectively.[148] It highlighted ease of use as an advantage of the MediaWiki-based system, noting that because the Wikimedia Foundation had been developing MediaWiki for a site aimed at the general public (Wikipedia), "its user interface was designed to be more user-friendly from start, and has received large user feedback over a long time", in contrast to DSpace's and OJS's focus on niche audiences.[148]

488 languages (not including languages that are supported but have no translations)

| Semantics | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||

| Semantics of programming languages |

||||||||

|

||||||||

The Semantic Web, sometimes known as Web 3.0 (not to be confused with Web3), is an extension of the World Wide Web through standards[1] set by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). The goal of the Semantic Web is to make Internet data machine-readable.

To enable the encoding of semantics with the data, technologies such as Resource Description Framework (RDF)[2] and Web Ontology Language (OWL)[3] are used. These technologies are used to formally represent metadata. For example, ontology can describe concepts, relationships between entities, and categories of things. These embedded semantics offer significant advantages such as reasoning over data and operating with heterogeneous data sources.[4] These standards promote common data formats and exchange protocols on the Web, fundamentally the RDF. According to the W3C, "The Semantic Web provides a common framework that allows data to be shared and reused across application, enterprise, and community boundaries."[5] The Semantic Web is therefore regarded as an integrator across different content and information applications and systems.

The term was coined by Tim Berners-Lee for a web of data (or data web)[6] that can be processed by machines[7]—that is, one in which much of the meaning is machine-readable. While its critics have questioned its feasibility, proponents argue that applications in library and information science, industry, biology and human sciences research have already proven the validity of the original concept.[8]

Berners-Lee originally expressed his vision of the Semantic Web in 1999 as follows:

I have a dream for the Web [in which computers] become capable of analyzing all the data on the Web – the content, links, and transactions between people and computers. A "Semantic Web", which makes this possible, has yet to emerge, but when it does, the day-to-day mechanisms of trade, bureaucracy and our daily lives will be handled by machines talking to machines. The "intelligent agents" people have touted for ages will finally materialize.[9]

The 2001 Scientific American article by Berners-Lee, Hendler, and Lassila described an expected evolution of the existing Web to a Semantic Web.[10] In 2006, Berners-Lee and colleagues stated that: "This simple idea…remains largely unrealized".[11] In 2013, more than four million Web domains (out of roughly 250 million total) contained Semantic Web markup.[12]

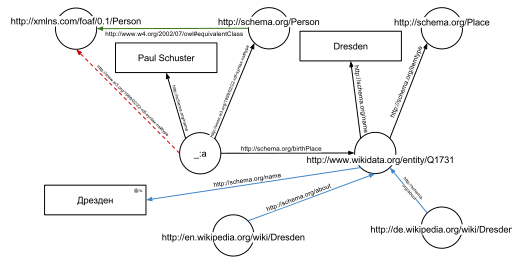

In the following example, the text "Paul Schuster was born in Dresden" on a website will be annotated, connecting a person with their place of birth. The following HTML fragment shows how a small graph is being described, in RDFa-syntax using a schema.org vocabulary and a Wikidata ID:

<div vocab="https://schema.org/" typeof="Person">

<span property="name">Paul Schuster</span> was born in

<span property="birthPlace" typeof="Place" href="https://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q1731">

<span property="name">Dresden</span>.

</span>

</div>

The example defines the following five triples (shown in Turtle syntax). Each triple represents one edge in the resulting graph: the first element of the triple (the subject) is the name of the node where the edge starts, the second element (the predicate) the type of the edge, and the last and third element (the object) either the name of the node where the edge ends or a literal value (e.g. a text, a number, etc.).

_:a <https://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#type> <https://schema.org/Person> .

_:a <https://schema.org/name> "Paul Schuster" .

_:a <https://schema.org/birthPlace> <https://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q1731> .

<https://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q1731> <https://schema.org/itemtype> <https://schema.org/Place> .

<https://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q1731> <https://schema.org/name> "Dresden" .

The triples result in the graph shown in the given figure.

One of the advantages of using Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs) is that they can be dereferenced using the HTTP protocol. According to the so-called Linked Open Data principles, such a dereferenced URI should result in a document that offers further data about the given URI. In this example, all URIs, both for edges and nodes (e.g. http://schema.org/Person, http://schema.org/birthPlace, http://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q1731) can be dereferenced and will result in further RDF graphs, describing the URI, e.g. that Dresden is a city in Germany, or that a person, in the sense of that URI, can be fictional.

The second graph shows the previous example, but now enriched with a few of the triples from the documents that result from dereferencing https://schema.org/Person (green edge) and https://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q1731 (blue edges).

Additionally to the edges given in the involved documents explicitly, edges can be automatically inferred: the triple

_:a <https://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#type> <http://schema.org/Person> .

from the original RDFa fragment and the triple

<https://schema.org/Person> <http://www.w3.org/2002/07/owl#equivalentClass> <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/Person> .

from the document at https://schema.org/Person (green edge in the figure) allow to infer the following triple, given OWL semantics (red dashed line in the second Figure):

_:a <https://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#type> <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/Person> .

The concept of the semantic network model was formed in the early 1960s by researchers such as the cognitive scientist Allan M. Collins, linguist Ross Quillian and psychologist Elizabeth F. Loftus as a form to represent semantically structured knowledge. When applied in the context of the modern internet, it extends the network of hyperlinked human-readable web pages by inserting machine-readable metadata about pages and how they are related to each other. This enables automated agents to access the Web more intelligently and perform more tasks on behalf of users. The term "Semantic Web" was coined by Tim Berners-Lee,[7] the inventor of the World Wide Web and director of the World Wide Web Consortium ("W3C"), which oversees the development of proposed Semantic Web standards. He defines the Semantic Web as "a web of data that can be processed directly and indirectly by machines".

Many of the technologies proposed by the W3C already existed before they were positioned under the W3C umbrella. These are used in various contexts, particularly those dealing with information that encompasses a limited and defined domain, and where sharing data is a common necessity, such as scientific research or data exchange among businesses. In addition, other technologies with similar goals have emerged, such as microformats.

Many files on a typical computer can be loosely divided into either human-readable documents, or machine-readable data. Examples of human-readable document files are mail messages, reports, and brochures. Examples of machine-readable data files are calendars, address books, playlists, and spreadsheets, which are presented to a user using an application program that lets the files be viewed, searched, and combined.

Currently, the World Wide Web is based mainly on documents written in Hypertext Markup Language (HTML), a markup convention that is used for coding a body of text interspersed with multimedia objects such as images and interactive forms. Metadata tags provide a method by which computers can categorize the content of web pages. In the examples below, the field names "keywords", "description" and "author" are assigned values such as "computing", and "cheap widgets for sale" and "John Doe".

<meta name="keywords" content="computing, computer studies, computer" />

<meta name="description" content="Cheap widgets for sale" />

<meta name="author" content="John Doe" />

Because of this metadata tagging and categorization, other computer systems that want to access and share this data can easily identify the relevant values.

With HTML and a tool to render it (perhaps web browser software, perhaps another user agent), one can create and present a page that lists items for sale. The HTML of this catalog page can make simple, document-level assertions such as "this document's title is 'Widget Superstore'", but there is no capability within the HTML itself to assert unambiguously that, for example, item number X586172 is an Acme Gizmo with a retail price of €199, or that it is a consumer product. Rather, HTML can only say that the span of text "X586172" is something that should be positioned near "Acme Gizmo" and "€199", etc. There is no way to say "this is a catalog" or even to establish that "Acme Gizmo" is a kind of title or that "€199" is a price. There is also no way to express that these pieces of information are bound together in describing a discrete item, distinct from other items perhaps listed on the page.

Semantic HTML refers to the traditional HTML practice of markup following intention, rather than specifying layout details directly. For example, the use of <em> denoting "emphasis" rather than <i>, which specifies italics. Layout details are left up to the browser, in combination with Cascading Style Sheets. But this practice falls short of specifying the semantics of objects such as items for sale or prices.

Microformats extend HTML syntax to create machine-readable semantic markup about objects including people, organizations, events and products.[13] Similar initiatives include RDFa, Microdata and Schema.org.

The Semantic Web takes the solution further. It involves publishing in languages specifically designed for data: Resource Description Framework (RDF), Web Ontology Language (OWL), and Extensible Markup Language (XML). HTML describes documents and the links between them. RDF, OWL, and XML, by contrast, can describe arbitrary things such as people, meetings, or airplane parts.

These technologies are combined in order to provide descriptions that supplement or replace the content of Web documents. Thus, content may manifest itself as descriptive data stored in Web-accessible databases,[14] or as markup within documents (particularly, in Extensible HTML (XHTML) interspersed with XML, or, more often, purely in XML, with layout or rendering cues stored separately). The machine-readable descriptions enable content managers to add meaning to the content, i.e., to describe the structure of the knowledge we have about that content. In this way, a machine can process knowledge itself, instead of text, using processes similar to human deductive reasoning and inference, thereby obtaining more meaningful results and helping computers to perform automated information gathering and research.

An example of a tag that would be used in a non-semantic web page:

<item>blog</item>

Encoding similar information in a semantic web page might look like this:

<item rdf:about="https://example.org/semantic-web/">Semantic Web</item>

Tim Berners-Lee calls the resulting network of Linked Data the Giant Global Graph, in contrast to the HTML-based World Wide Web. Berners-Lee posits that if the past was document sharing, the future is data sharing. His answer to the question of "how" provides three points of instruction. One, a URL should point to the data. Two, anyone accessing the URL should get data back. Three, relationships in the data should point to additional URLs with data.

Tags, including hierarchical categories and tags that are collaboratively added and maintained (e.g. with folksonomies) can be considered part of, of potential use to or a step towards the semantic Web vision.[15][16][17]

Unique identifiers, including hierarchical categories and collaboratively added ones, analysis tools and metadata, including tags, can be used to create forms of semantic webs – webs that are to a certain degree semantic.[18] In particular, such has been used for structuring scientific research i.a. by research topics and scientific fields by the projects OpenAlex,[19][20][21] Wikidata and Scholia which are under development and provide APIs, Web-pages, feeds and graphs for various semantic queries.

Tim Berners-Lee has described the Semantic Web as a component of Web 3.0.[22]

People keep asking what Web 3.0 is. I think maybe when you've got an overlay of scalable vector graphics – everything rippling and folding and looking misty – on Web 2.0 and access to a semantic Web integrated across a huge space of data, you'll have access to an unbelievable data resource …

— Tim Berners-Lee, 2006

"Semantic Web" is sometimes used as a synonym for "Web 3.0",[23] though the definition of each term varies.

The next generation of the Web is often termed Web 4.0, but its definition is not clear. According to some sources, it is a Web that involves artificial intelligence,[24] the internet of things, pervasive computing, ubiquitous computing and the Web of Things among other concepts.[25] According to the European Union, Web 4.0 is "the expected fourth generation of the World Wide Web. Using advanced artificial and ambient intelligence, the internet of things, trusted blockchain transactions, virtual worlds and XR capabilities, digital and real objects and environments are fully integrated and communicate with each other, enabling truly intuitive, immersive experiences, seamlessly blending the physical and digital worlds".[26]

Some of the challenges for the Semantic Web include vastness, vagueness, uncertainty, inconsistency, and deceit. Automated reasoning systems will have to deal with all of these issues in order to deliver on the promise of the Semantic Web.

This list of challenges is illustrative rather than exhaustive, and it focuses on the challenges to the "unifying logic" and "proof" layers of the Semantic Web. The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) Incubator Group for Uncertainty Reasoning for the World Wide Web[27] (URW3-XG) final report lumps these problems together under the single heading of "uncertainty".[28] Many of the techniques mentioned here will require extensions to the Web Ontology Language (OWL) for example to annotate conditional probabilities. This is an area of active research.[29]

Standardization for Semantic Web in the context of Web 3.0 is under the care of W3C.[30]

The term "Semantic Web" is often used more specifically to refer to the formats and technologies that enable it.[5] The collection, structuring and recovery of linked data are enabled by technologies that provide a formal description of concepts, terms, and relationships within a given knowledge domain. These technologies are specified as W3C standards and include:

The Semantic Web Stack illustrates the architecture of the Semantic Web. The functions and relationships of the components can be summarized as follows:[31]

Well-established standards:

Not yet fully realized:

The intent is to enhance the usability and usefulness of the Web and its interconnected resources by creating semantic web services, such as:

<meta> tags used in today's Web pages to supply information for Web search engines using web crawlers). This could be machine-understandable information about the human-understandable content of the document (such as the creator, title, description, etc.) or it could be purely metadata representing a set of facts (such as resources and services elsewhere on the site). Note that anything that can be identified with a Uniform Resource Identifier (URI) can be described, so the semantic web can reason about animals, people, places, ideas, etc. There are four semantic annotation formats that can be used in HTML documents; Microformat, RDFa, Microdata and JSON-LD.[35] Semantic markup is often generated automatically, rather than manually.

Such services could be useful to public search engines, or could be used for knowledge management within an organization. Business applications include:

In a corporation, there is a closed group of users and the management is able to enforce company guidelines like the adoption of specific ontologies and use of semantic annotation. Compared to the public Semantic Web there are lesser requirements on scalability and the information circulating within a company can be more trusted in general; privacy is less of an issue outside of handling of customer data.

Critics question the basic feasibility of a complete or even partial fulfillment of the Semantic Web, pointing out both difficulties in setting it up and a lack of general-purpose usefulness that prevents the required effort from being invested. In a 2003 paper, Marshall and Shipman point out the cognitive overhead inherent in formalizing knowledge, compared to the authoring of traditional web hypertext:[46]

While learning the basics of HTML is relatively straightforward, learning a knowledge representation language or tool requires the author to learn about the representation's methods of abstraction and their effect on reasoning. For example, understanding the class-instance relationship, or the superclass-subclass relationship, is more than understanding that one concept is a "type of" another concept. [...] These abstractions are taught to computer scientists generally and knowledge engineers specifically but do not match the similar natural language meaning of being a "type of" something. Effective use of such a formal representation requires the author to become a skilled knowledge engineer in addition to any other skills required by the domain. [...] Once one has learned a formal representation language, it is still often much more effort to express ideas in that representation than in a less formal representation [...]. Indeed, this is a form of programming based on the declaration of semantic data and requires an understanding of how reasoning algorithms will interpret the authored structures.

According to Marshall and Shipman, the tacit and changing nature of much knowledge adds to the knowledge engineering problem, and limits the Semantic Web's applicability to specific domains. A further issue that they point out are domain- or organization-specific ways to express knowledge, which must be solved through community agreement rather than only technical means.[46] As it turns out, specialized communities and organizations for intra-company projects have tended to adopt semantic web technologies greater than peripheral and less-specialized communities.[47] The practical constraints toward adoption have appeared less challenging where domain and scope is more limited than that of the general public and the World-Wide Web.[47]

Finally, Marshall and Shipman see pragmatic problems in the idea of (Knowledge Navigator-style) intelligent agents working in the largely manually curated Semantic Web:[46]

In situations in which user needs are known and distributed information resources are well described, this approach can be highly effective; in situations that are not foreseen and that bring together an unanticipated array of information resources, the Google approach is more robust. Furthermore, the Semantic Web relies on inference chains that are more brittle; a missing element of the chain results in a failure to perform the desired action, while the human can supply missing pieces in a more Google-like approach. [...] cost-benefit tradeoffs can work in favor of specially-created Semantic Web metadata directed at weaving together sensible well-structured domain-specific information resources; close attention to user/customer needs will drive these federations if they are to be successful.

Cory Doctorow's critique ("metacrap")[48] is from the perspective of human behavior and personal preferences. For example, people may include spurious metadata into Web pages in an attempt to mislead Semantic Web engines that naively assume the metadata's veracity. This phenomenon was well known with metatags that fooled the Altavista ranking algorithm into elevating the ranking of certain Web pages: the Google indexing engine specifically looks for such attempts at manipulation. Peter Gärdenfors and Timo Honkela point out that logic-based semantic web technologies cover only a fraction of the relevant phenomena related to semantics.[49][50]

Enthusiasm about the semantic web could be tempered by concerns regarding censorship and privacy. For instance, text-analyzing techniques can now be easily bypassed by using other words, metaphors for instance, or by using images in place of words. An advanced implementation of the semantic web would make it much easier for governments to control the viewing and creation of online information, as this information would be much easier for an automated content-blocking machine to understand. In addition, the issue has also been raised that, with the use of FOAF files and geolocation meta-data, there would be very little anonymity associated with the authorship of articles on things such as a personal blog. Some of these concerns were addressed in the "Policy Aware Web" project[51] and is an active research and development topic.

Another criticism of the semantic web is that it would be much more time-consuming to create and publish content because there would need to be two formats for one piece of data: one for human viewing and one for machines. However, many web applications in development are addressing this issue by creating a machine-readable format upon the publishing of data or the request of a machine for such data. The development of microformats has been one reaction to this kind of criticism. Another argument in defense of the feasibility of semantic web is the likely falling price of human intelligence tasks in digital labor markets, such as Amazon's Mechanical Turk.[citation needed]

Specifications such as eRDF and RDFa allow arbitrary RDF data to be embedded in HTML pages. The GRDDL (Gleaning Resource Descriptions from Dialects of Language) mechanism allows existing material (including microformats) to be automatically interpreted as RDF, so publishers only need to use a single format, such as HTML.

The first research group explicitly focusing on the Corporate Semantic Web was the ACACIA team at INRIA-Sophia-Antipolis, founded in 2002. Results of their work include the RDF(S) based Corese[52] search engine, and the application of semantic web technology in the realm of distributed artificial intelligence for knowledge management (e.g. ontologies and multi-agent systems for corporate semantic Web) [53] and E-learning.[54]

Since 2008, the Corporate Semantic Web research group, located at the Free University of Berlin, focuses on building blocks: Corporate Semantic Search, Corporate Semantic Collaboration, and Corporate Ontology Engineering.[55]

Ontology engineering research includes the question of how to involve non-expert users in creating ontologies and semantically annotated content[56] and for extracting explicit knowledge from the interaction of users within enterprises.

Tim O'Reilly, who coined the term Web 2.0, proposed a long-term vision of the Semantic Web as a web of data, where sophisticated applications are navigating and manipulating it.[57] The data web transforms the World Wide Web from a distributed file system into a distributed database.[58]

cite journal: Cite journal requires |journal= (help)cite book: |work= ignored (help)